I'm sure a lot of people think of "old movie" as a synonym for "long movie," thanks to the enduring popularity of films like

Gone With the Wind and

The Sound of Music, but the truth is that the average length of any given film hasn't changed much in the past eighty years -- if anything, films have actually gotten longer as time has gone by, not shorter. Films released prior to 1935 regularly clock in at just over one hour, whereas today, studios rarely greenlight anything shorter than an hour and a half, unless the brevity of the running time is part of the film's gimmick (

Cloverfield). One of my chief complaints about films released before 1950 is that they're often

too short, that they'll take their time building an interesting story, and then as soon as the story reaches its resolution, BOOM!, they're done, without giving you any time to process what just happened; contrast this with a contemporary film like

The Return of the King, which reaches a nice, slow, easy conclusion...and then another conclusion...and then another conclusion before the credits finally roll.

I mention all of this so that when I say that

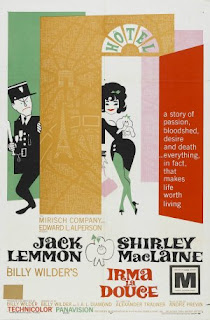

Irma La Douce is too long, people won't think that statement is a given just because it came out forty-eight years ago.

Irma La Douce is too long simply because it's too damn long, and because what starts out as an enjoyable if silly movie devolves into utter ridiculousness by the time its two and a half hours are up. Released in 1963, it is director Billy Wilder's adaptation of a musical play by Alexandre Breffort, and part of the problem is that it maintains the musical's fantastic aspects without maintaining any of the actual, you know,

music. This is charming at first, presenting a candy-colored but not necessarily unrealistic vision of Paris in the middle of the twentieth century, full of loud hookers and bumbling police and winky barmen who believe in living life to its fullest, but it wears thin as soon as an actual story starts to cohere and the natural tension between fantasy and reality explodes all over the screen. The thing about writing fantasy is that you can do just about anything you want, from talking animals to talking planets, so long as you abide by the rules

you establish at the story's outset; as soon as you break those rules, you're done; you've lost credibility. A story doesn't have to have any basis in reality, but it has to make its own kind of sense.

Say, for example, that your story is about a good-hearted, no-nonsense prostitute who looks at sleeping with men for money as a vocation, same as any other, and suffers no ill effects from her promiscuity, except maybe that she's become cynical toward the notion of domesticity. Fine. Not every story about a prostitute has to be a gritty melodrama. And let's say the prostitute falls in love with a goody-two-shoes former policeman and makes him her new pimp, but doesn't understand why he's bothered by her lifestyle. And let's also say that, in order to stop her from sleeping around, the cop impersonates a wealthy British john who eliminates her need for any other customers, and that the cop has to work multiple jobs in secret in order to pay her the money that she'll in turn give right back to him. Alright. Seems unlikely, but it

could happen. The story is far-fetched, even whimsical, but not impossible: those are the perimeters it sets up for itself, and for roughly the first two hours, those are the perimeters that the story -- also known as

Irma La Douce -- follows.

Then, suddenly, in the film's last act, not only do the wheels come off, they give way to jet packs powered by unicorn farts that rocket the story straight to the moon. Suddenly the cop can bend steel bars; suddenly he can hold his breath under water indefinitely; suddenly the police can't recognize the man they're looking for because he's wearing one of their uniforms. Suddenly we're watching a full-out farce instead of a light comedy. The end of

Irma La Douce is an absolute mess, and not even a funny mess; the comedy that buoys the rest of the film gives way to an off-putting strangeness that can only hope to make you laugh because it makes so little sense. Irma is pregnant! She's having the baby at the altar! The police force wants the cop back because...because! The whole progression is a non sequitur, like if I suddenly ended this review on a positive note!

Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine both give great performances, that's for sure.

Grade: C+